Women and the Decade of Centenaries

11 March 2021

The events of 1912–23 remembered during the ‘Decade of Centenaries’ have traditionally been presented as a story dominated by men. Much ink has been spilled over the past century chronicling the lives, actions and legacies of the likes of Edward Carson, Michael Collins, James Connolly and James Craig, but the role of women has been often either dismissed as peripheral or entirely overlooked.

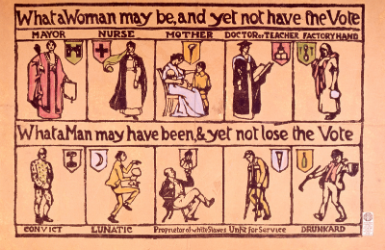

Women from all classes and communities played central roles in the events of this turbulent period. From the female Unionist leagues who marshalled opposition to Home Rule, to the militant activities of Cumann na mBan, this period cannot be fully understood without recognising that women were also political actors even if the political system excluded them from formal political roles. The political positions of British and Irish women also intersected with other forms of politics, such as questions surrounding female enfranchisement, trade unionism, pacifism and internationalism that could complement and challenge views on the constitutional question.

Below is a snapshot of women who played significant roles in the events of 1912–23. It includes women from Catholic and Protestant, Nationalist and Unionist backgrounds, who advocated fiercely for their respective political and religious beliefs. Yet they do not always fit easily into the expectations and stereotypes associated with these labels.

Though often associated with Catholicism, Irish nationalism attracted many Irish Protestants, several of whom were from Ulster. The Gaelic Revival from which Irish nationalism drew much of its strength would have foundered without the efforts of Irish Protestants, several of whom were women. Similarly, Unionist women were frequently at the forefront of campaigns for women’s education, suffrage and advancement, drawing on the longer history of British Liberalism within Ulster and across the United Kingdom, yet their efforts could be challenged by other Unionist women who played important roles in anti-suffrage campaigns and in promoting conservative values.

These are far from the only women associated with the Decade of Centenaries. But their stories give a flavour of how women were not only shaped by this period of momentous change, but shaped the very events that took place.

Isabella Tod (1836–1896)

Isabella Tod was a women’s rights campaigner and Liberal Unionist activist. Born in Scotland, little is known about her until the 1850s, when she moved to Belfast with her mother, who hailed from Co. Monaghan. By the 1860s Tod was actively campaigning for greater equality for women, establishing the Ladies’ Institute in Belfast in 1867, which provided classes for young women interested in improving their education. Tod was instrumental in ensuring that girls were included in the 1878 Intermediate Education Act, which paved the way for permitting women to attend university.

Her activism was not restricted to education. In 1871 she established the North of Ireland Women’s Suffrage Committee, the first suffrage society in Ireland, and was a leading campaigner for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Act. Tod was vehemently opposed to Irish Home Rule, believing that it would undo the social reforms she had struggled to achieve. The last ten years of her life were dedicated to campaigning against Gladstone’s 1886 Home Rule Bill.

Alice Stopford Green (1847–1922)

Alice Stopford Green was a historian and Irish nationalist, born into an Anglican family in Co. Meath. In 1874 her family moved to Chester, where she met the historian John Richard Green, whom she married three years later. Following Green’s death in 1883, Stopford Green dedicated herself to historical writing. She became involved in agitating against the Boer War and colonial policy in Africa at the same time as she became interested in the history of Ireland. Her most important works include Irish Nationality (1911), The Old Irish World (1912) and History of the Irish State to 1014 (1925).

In 1914 she became involved in importing arms into Ireland on behalf of the Irish Volunteers, but opposed the 1916 Rebellion and remained uncomfortable with using violence to achieve independence. She supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty and became a member of the senate of the Irish Free State.

Theresa Susey Helen Chetwynd Talbot, Marchioness of Londonderry (1856–1919)

Theresa was an anti-suffragist, political activist, and hostess. The wife of Lord Charles Castlereagh, heir to the Londonderry marquessate, she was intimately involved in the political life of the last quarter of the 19th century. She was on the Grand Council of the Primrose League, which promoted grassroots Conservatism to women through the means of entertainment.

A prominent critic of the campaigns for Irish Home Rule, in 1893 she organised a petition opposing it, signed by just under 20,000 Ulster women. By virtue of her contacts and access to finance, she helped to turn the newly created Ulster Women’s Unionist Council (1911) into a formidable organisation across both Britain and Ireland, becoming its president in 1913. She was an ardent anti-suffragist and played an important role in pressuring other Unionist women to reject the franchise.

Ada McNeill (1860–1959)

Born in England but brought up in the Antrim coastal village of Cushendun, Ada McNeill, commonly known throughout the Glens as Miss Ada, was one of several affluent Protestant women who played an important role in the Gaelic Revival in Antrim. She founded the Gaelic cultural festival Feis na nGleann (‘The Glens Feis’) in 1904, and was a founding member of the Ulster College of Irish in Cloughaneely, Donegal.

McNeill was raised in a staunchly Unionist household, but she rejected her family’s political views, joining the Gaelic League and actively promoting the Irish language throughout the Glens. She was a close friend of Roger Casement and visited the Easter Rising leader in Brixton prison before his execution in 1916. Following partition, ‘Miss Ada’ continued to promote the Irish language in Antrim and regularly read Irish folklore to school pupils in Cushendun.

Julia McMordie (née Gray) (1860–1942)

Julia McMordie was a Unionist politician, social reformer and philanthropist. Born in County Durham to a wealthy Presbyterian shipbuilding family, she moved to Belfast in 1886 following her marriage to Robert James McMordie, who would serve as the city’s Lord Mayor and Ulster Unionist MP for East Belfast from 1910 to 1914. McMordie was involved in a range of charitable organisations in Belfast, including the Girls’ Help Society and the Ulster Hospital for Women and Children.

She was an active member of the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council, serving as vice-president from 1919 until her death in 1942. Despite opposing the campaigns for women’s suffrage, in 1921 McMordie was elected to the first Northern Ireland parliament. She used her maiden speech in 1922 to call for an increase in the number of women police officers, and campaigned repeatedly to improve educational provisions, particularly through employing specially trained teachers for disabled children.

Alice Milligan (1866–1953)

An author, dramatist and poet, Alice Milligan was a leading figure in the Gaelic Revival and the Irish nationalist movement at the turn of the 20th century, championing the right of Protestants to participate in Irish nationalism. Born into a Methodist family in Omagh, Co. Tyrone, Milligan began to learn Irish in 1888 while living in Dublin.

In 1896, along with Anna Johnston, Milligan founded and edited the Shan Van Vocht, an influential political and literary periodical which cultivated the various strands of Irish nationalist thought. Following the partition of Ireland in 1921 Milligan fled Dublin after her brother William, a former British army officer, was ordered to leave the city by republicans. Struggling under increasing financial pressures, Milligan eventually resettled in Tyrone in 1931, where she lived under constant state surveillance.

Constance Markievicz (née Gore-Booth) (1868–1927)

Constance Markievicz was a nationalist, feminist, revolutionary and socialist. Born into an Anglo-Irish landed family in Sligo, from 1893 she studied at the Slade School of Art in London. In 1900 she married Casimir Markievicz, an artist from a wealthy Polish family from Ukraine. By this time she had joined the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and later got involved in nationalist politics through her membership of Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland).

She joined James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army, in whose ranks she was active during the 1916 Rising. Markievicz was the first woman to be elected to the Westminster parliament in 1918, though she did not take her seat. She was Minister for Labour in Dáil Éireann from 1919 to 1922. Vehemently opposing the Anglo-Irish Treaty, she acted as propagandist for the republican cause before becoming an Irish TD for Fianna Fáil.

Eva Gore-Booth (1870–1926)

The younger sister of Constance Markievicz, Eva Gore-Booth was a trade unionist, feminist, suffragist and poet. In 1896 she met Esther Roper, a Manchester-based social activist and suffragist, with whom she formed an immediate and life-long relationship, and in 1897 she settled in Manchester with Roper.

There she became active in promoting the concerns of working women. She played important roles in campaigning for the rights of a wide range of working women, including pit brow workers, women acrobats, Oxford Circus flower sellers, and barmaids – in that campaign Eva and Constance managed to unseat Winston Churchill from what should have been a safe by-election victory in Manchester North-West in 1906. Gore-Booth travelled to Dublin after the Rising, playing an important role in campaigning for the reprieve of her sister’s death sentence and improvement of prison conditions.

Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington (1877–1946)

A feminist, suffragette, nationalist campaigner and teacher, Hanna Sheehy was born in Cork to a mill owner, but moved to Dublin in 1887. She studied Modern Languages at the Royal University of Ireland, graduating in 1899. She took an MA in 1902, and in 1903 married Francis Skeffington, each taking the other’s names. In 1908 she co-founded the Irish Women’s Franchise League, which paralleled the militant activities of the Pankhurts’ British Women’s Social and Political Union (the Suffragettes).

In 1919, she was elected as a Sinn Féin candidate to Dublin Corporation and took the republican side in the civil war, campaigning across the USA for funds to relieve families of republican soldiers. In 1926 she was appointed to the executive of the new Fianna Fáil party and, in 1937, actively campaigned against the recently promulgated Irish Constitution.

Dehra Chichester (later Dame Dehra Parker) (1882–1963)

Dehra Chichester was the longest-serving female MP in the Northern Ireland parliament. Born in India and brought up in Kilrea, Co. Londonderry, she was educated in the United States and later in Germany. In 1911 she married the Unionist MP Robert Peel Dawson Spencer Chichester. She shared his staunch Unionist views, playing a central role in the formation of the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council in 1911.

Robert Chichester died in 1921, the same year that Dehra was one of two women to be elected to the inaugural Northern Ireland parliament. She resigned her seat in 1929, but was returned in 1933 as Ulster Unionist member for South Londonderry, which she held continuously until her retirement in 1960. In 1949 she was appointed minister for health and local government, overseeing the implementation of the National Health Service in Northern Ireland.

Edith Helen Vane-Tempest Stewart, Marchioness of Londonderry (1879–1959)

A hostess, political influencer and (unlike her sister Theresa) suffragist, Edith was the daughter of Tory MP Henry Chaplin. In 1899 she married Charles Stewart Henry Vane-Tempest-Stewart, son of the 6th marquess of Londonderry, one of the richest and most politically powerful families in the United Kingdom. During the First World War she established the Women’s Legion, which deployed women in agricultural and industrial work to free up men for the front.

Edith used the work of the Women’s Legion to advance the cause of women’s suffrage, for which she was a fierce campaigner. At various times she was vice-president of the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council, chairman of the NI branch of the Institute of District Nursing, and Justice of the Peace in Co. Down and Durham. She was also a prominent London hostess, establishing an executive dining club frequented by every UK prime minister during the 1930s and members of the monarchy.