The Partition of Ireland: Context and Content

28 January 2021

Dr Marie Coleman, School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics, Queen’s University Belfast.

When the First World War ended in 1918 the British government had to revisit the question of the constitutional status of Ireland, which had been shelved for the duration of the war, following the enactment and immediate suspension of the third Home Rule bill in September 1914.

The political position in parliament had changed dramatically in the intervening period. Following the 1918 general election, the Irish Parliamentary [Home Rule] Party was reduced to a rump of seven MPs, and while the Liberal Party leader, David Lloyd George, remained as Prime Minister, there was a Conservative majority in the government.

This would ensure that the position of Ulster unionists was protected. The status of unionists was further enhanced by the fact that a former unionist leader, Walter Long, was the cabinet’s chief Irish adviser and chairman of the committee charged with producing new legislation to determine Ireland’s place within the union.

Two Parliaments

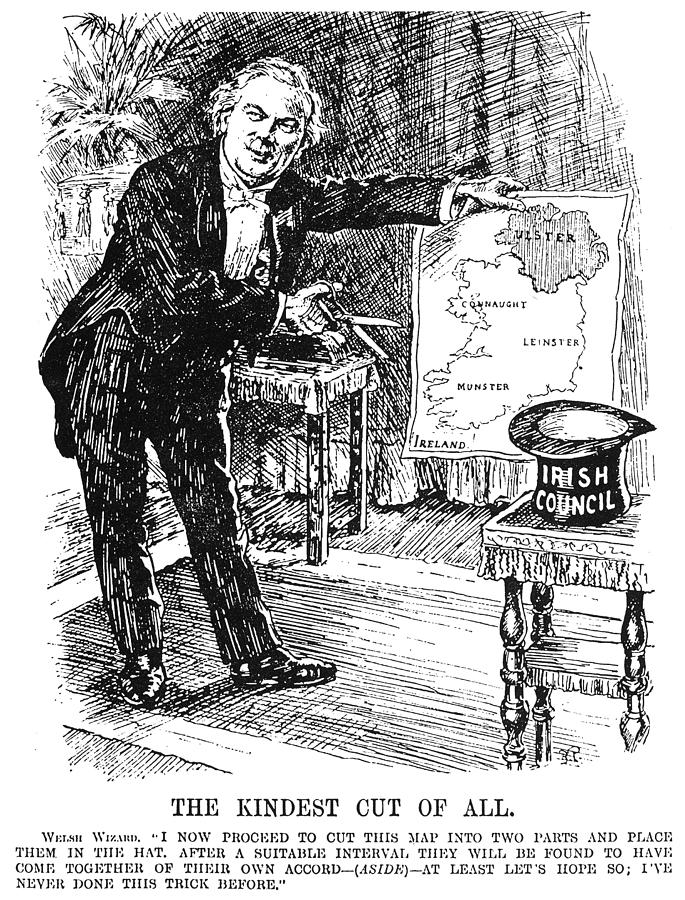

The Long Committee reported in November 1919, recommending the repeal of the 1914 Government of Ireland Act (third Home Rule bill) and its replacement with a new one. Long’s proposals envisaged two Home Rule parliaments, one based in Belfast with jurisdiction over all nine counties of Ulster and one in Dublin that would govern the remaining 23 counties.

An idea known as county option, that would have allowed individual counties to hold plebiscites to decide whether to opt in or out of Home Rule was rejected as unworkable and likely to exacerbate sectarian sentiment in those Ulster counties such as Fermanagh and Tyrone that had Catholic majorities.

The suggestion of a separate Home Rule parliament for a nine-county Ulster was significant. It was a recognition of how unionist opinion had changed since 1912. At the outset of the third Home Rule crisis unionists were implacably opposed to Home Rule for any part of Ireland, preferring to remain an integral part of the United Kingdom.

Since then they had faced the reality that the British government was prepared to alter the union by implementing Irish Home Rule. The changing political attitudes of nationalist Ireland also convinced them that they had no desire to remain part of the same political entity. In the eyes of unionists, nationalists’ loyalty during the war was questionable, especially in view of their opposition to conscription, and the armed uprising against British rule at Easter 1916 was further testament to their treachery. By 1920, while most unionists would still have preferred to remain within the union, they had realised that the best chance of protecting their own interest lay in self-government for Ulster.

The nine-county Ulster recommended by the Long Committee was not that favoured by Ulster unionists. In 1911, 43 per cent of the entire province of Ulster was Roman Catholic, whereas the Catholic population of the six counties with the largest Protestant populations was only 34 per cent.

The third option for Ulster unionists would be to take control of only four counties – Antrim, Armagh, Derry and Down – excluding the most contentious counties of Tyrone and Fermanagh, which had slight Catholic majorities of around 55 per cent. However, such an entity would be too small to survive economically or politically. The opposition of the Ulster unionists and their influence with the Conservative-controlled government ensured that a six-county Ulster was the solution adopted.

The Government of Ireland Act

The Government of Ireland Act was passed on 23 December 1920 and partitioned Ireland into two Home Rule entities to be called Northern Ireland (comprising counties Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone) and Southern Ireland, which contained the remaining 26 counties. The powers of the legislatures of both jurisdictions were similar to those envisaged for the Irish Home Rule parliament under the 1914 act, and considerable powers over defence, finance and trade were reserved for Westminster.

The lack of effective taxation powers would prove to be a serious problem for the Northern Ireland government during the 1920s and 1930s. The inclusion of a plan to establish a Council of Ireland ‘to make orders with respect to matters affecting interests both in Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland’, and a clause outlining how a parliament for the whole of Ireland might be established, indicated that the government never intended partition to be a permanent solution. These were envisaged as subordinate legislatures with section 75 of the act asserting that the ‘supreme authority of the Parliament of the United Kingdom shall remain unaffected and undiminished’.

A number of safeguards were inserted to protect both the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland and the Protestant minority in Southern Ireland. These included a prohibition on the endowment of religion or interfering with educational rights on religious grounds, clauses that had also been in the 1914 act; and the use of proportional representation by single transferable vote (PRSTV) to elect the members of both Houses of Commons.

This latter provision was designed to ensure that minority political parties would secure adequate parliamentary representation; the British government did not intend a Sinn Féin-style landslide like 1918 to recur in Ireland. The provision remained in Northern Ireland until 1929 when it was repealed, in the face of labour unionist opposition to the ruling Ulster Unionist Party. The abolition of PR in Northern Ireland reinforced unionist dominance and remained a grievance for nationalists. PRSTV remains the electoral system in the Republic of Ireland.

Partition Enacted

The Government of Ireland Act came into operation on 3 May 1921. Elections for both parliaments were held, although Sinn Féin refused to recognize the new national political entity of Southern Ireland and deemed the election to be a contest for the second Dáil Éireann. Neither Labour or the remnant of the Irish Parliamentary Party contested the election and all 124 Sinn Féin candidates were returned unopposed. Four independent southern unionists were returned unopposed for the Dublin University (Trinity College) constituency.

In Northern Ireland, 40 of the 52 seats in the House of Commons were taken by unionists, with Sinn Féin and the Nationalists (effectively the old Home Rulers) taking six each. Sinn Féin’s northern MPs, including Collins, de Valera and Griffith, did not take their seats in the new Northern Ireland parliament which was opened by King George V in City Hall, Belfast on 22 June 1921.

Home Rule had finally been implemented in Ireland, but ironically it was the Ulster unionists who had been so strongly opposed to the idea a decade previously upon whom it was conferred. The partition of Ireland was now a reality. The British government had solved the Ulster part of the Irish question and could now concentrate on seeking a peaceful settlement with Sinn Féin in the south.

The relationship between ‘Southern Ireland’ and the United Kingdom was established under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty signed in December 1921, under which the 26 counties became a dominion of the commonwealth known as the Irish Free State (later evolving into the sovereign Republic of Ireland in 1949).

The treaty included a provision for a boundary commission to determine the final border between the two Irish jurisdictions, but its deliberations in 1925 did not result in any alterations being made and the dividing line established under the 1920 legislation remains in place over one hundred years later. As the United Kingdom’s only land border, shared with a European Union member state, it has gained renewed significance since the Brexit referendum in 2016.